ARPANET Adopts TCP/IP

The modern internet emerges as ARPANET transitions to the TCP/IP protocol, unifying previously separate networks.

Who got online, who didn’t — and why it still matters.

The internet is considered to have been “born” on January 1, 1983, when ARPANET officially adopted the TCP/IP protocol suite, switched from the older Network Controller Protocol (NCP), transforming a patchwork of networks into a unified system. The Defense Communication Agency decided to separate the network, making it public (“ARPANET”) and classified (“MILNET”).

The system became accessible to the public in 1989, when Tim Berners-Lee created the World Wide Web in Switzerland at CERN. European Organization for Nuclear Research (in French Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire) was founded in 1952 as a global collaboration hub where thousands of scientists conduct ground-breaking research, advancing knowledge and peace.

Tim Berners-Lee’s invention of the World Wide Web launched the dawn of internet usage. The world’s first website was published in 1991 and the first web browser (Mosaic) was available in 1993, developed by Marc Andreessen and Eric Bina working at the NSF-supported National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

The 1990s marked the dawn of the internet age, but access was uneven. Geographic location, racial identity, and socioeconomic status dictated who logged on — and who was left behind. This website explores the early digital divide through maps, media, and data from the decade that wired the world.

The National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) within the Department of Commerce published a series of reports documenting disparities in universal home telephone service, computer ownership and internet access. The first report was Falling Through the Net, focused on home telephone penetration.

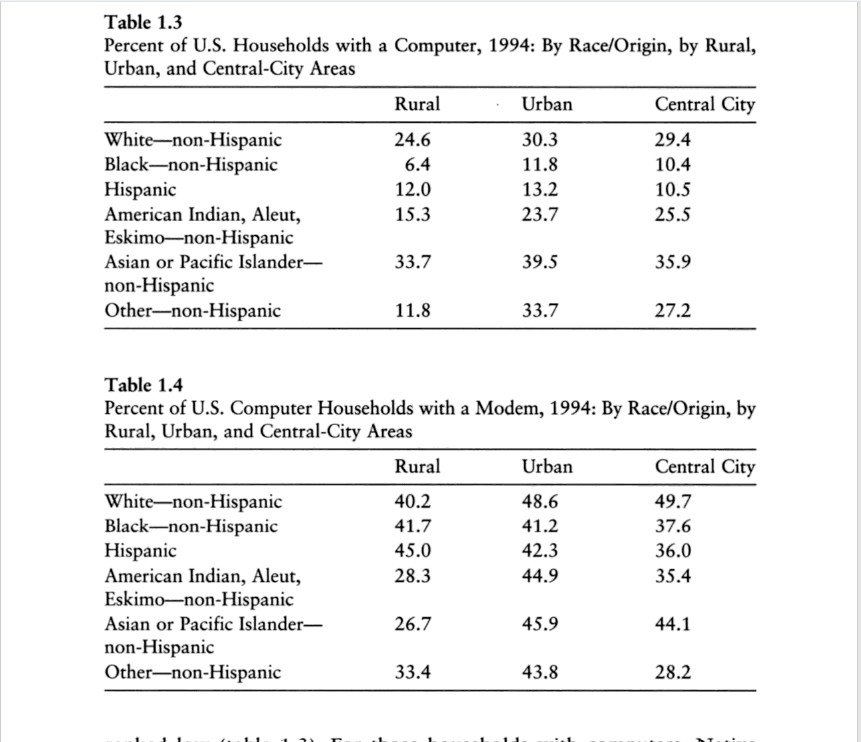

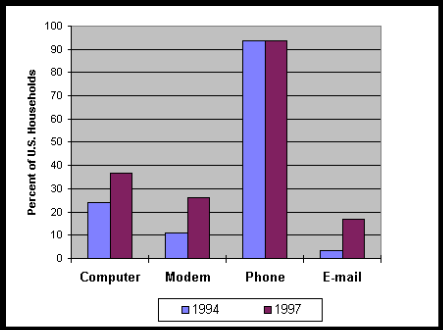

In July 1994, the NTIA contacted the Census Bureau and the Federal Communication Commission (FCC) requesting them to add questions on computer/modem ownership and usage to the second survey. NTIA also requested the Census Bureau to cross-reference information gathered according to variables such as age, income, education level, race and geographic locations (central city, rural and urban).

NTIA’s 1994 expansion of computer and modem questions helped define the early digital divide.

By adding this additional information to the survey, NTIA’s database created a more detailed profile of universal service in the United States that included telephones, computers and modems.

President Bill Clinton’s 2000 State of the Union Address placed the “digital divide” at the center of national policy discussions, warning that unequal access to technology threatened to deepen existing inequalities. The “digital divide” refers to the gap between individuals, households, businesses, or geographic areas that have access to information and communication technologies — such as computers, broadband, and the internet — and those that do not. It highlights inequalities in both access and effective use of technology.

At the same time, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) published its Falling Through the Net series (1995–2000), documenting disparities in computer ownership and internet connectivity across geography, race, and class. Together, these sources framed the digital divide as both a technological and social challenge.

I will examine how rural infrastructure, income inequality, and systemic barriers influenced internet adoption — and how those patterns echo in today’s broadband debates. From dial-up modems to policy memos, this is a story of connection, exclusion, and the infrastructure of inequality.

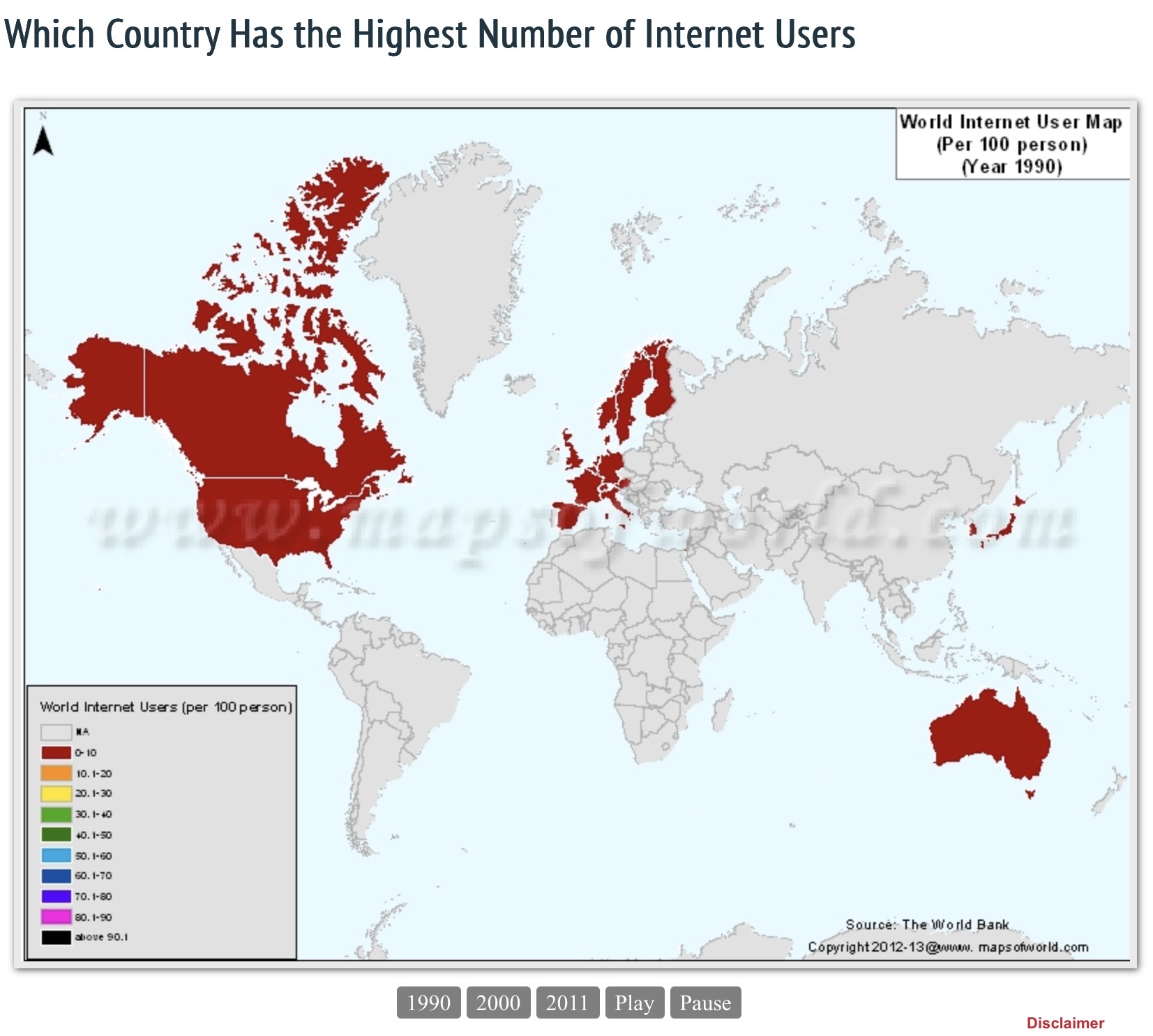

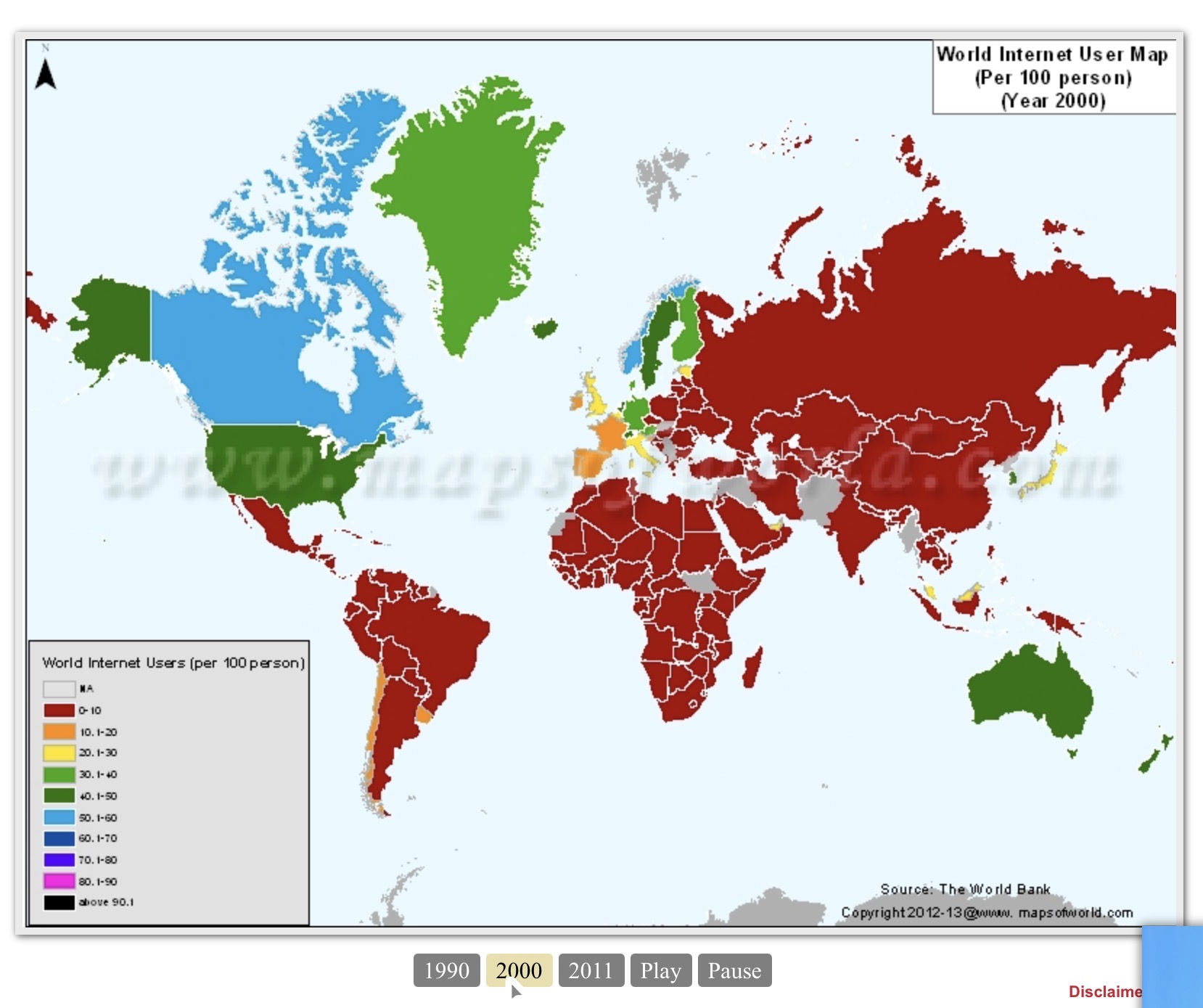

Early patterns of computer and internet adoption across U.S. regions in the 1990s.

Regional disparities in connectivity during the rise of the 1990s internet.

Rural households often faced limited infrastructure, with fewer internet service providers and slower dial-up connections. Urban households, by contrast, benefited from denser markets where providers competed to expand access, making connectivity more affordable and widespread. This structural imbalance meant that geography itself became a key determinant of whether families could participate in emerging digital technology.

The lack of access had practical consequences: rural residents were less able to use online resources for education, job searches, and healthcare information. The divide also reflected broader economic inequalities, as rural areas often had lower household incomes and fewer educational institutions equipped with computers. Policymakers recognized that without intervention, rural communities risked being excluded from the opportunities the internet promised, deepening existing social and economic divides. (Reference table 1.5)

Table from MIT’s The Digital Divide (pg. 11) comparing rural and urban connectivity.

Federal investments aimed to “close the digital divide” by wiring schools, libraries, and rural communities. The E-rate program, created in 1996 under the Telecommunications Act, subsidized internet access for educational institutions, particularly those serving underserved populations. These initiatives expanded connectivity nationwide, yet NTIA’s data revealed that geography remained a persistent obstacle. The urban-rural gap of the 1990s not only limited opportunities for rural households at the time but also set the stage for today’s broadband equity debates, where extending reliable access to rural America continues to be a central challenge in achieving universal digital inclusion.

Race and ethnicity were central factors in shaping the digital divide of the 1990s, with NTIA’s Falling Through the Net reports consistently showing that Black and Latino households had significantly lower rates of computer ownership and internet access compared to White and Asian households. These disparities reflected broader patterns of income inequality, educational opportunity, and systemic barriers to technology adoption.

NTIA’s 1995 and 1998 Falling Through the Net reports highlighted that race and ethnicity were strong predictors of who could connect to the internet. White and Asian households were more likely to own computers and subscribe to internet services, while Black and Latino households lagged behind. For example, the 1998 report noted that “there is still a significant digital divide based on race, income, and other demographic characteristics” (NTIA, 1998).

The racial digital divide had profound consequences. Communities with lower connectivity were less able to access online job postings, educational resources, and emerging e-commerce opportunities. The divide risked reinforcing existing inequalities, as those already disadvantaged by systemic racism were further excluded from the benefits of the information age.

This exclusion was not only about access but also about usage: even when minority households had computers, they often lacked the digital literacy training or institutional support to use them effectively. The divide thus became both a technological and social barrier, limiting participation in the new digital age.

Percentage of U.S. households with computer access by race, highlighting major disparities during the 1990s.

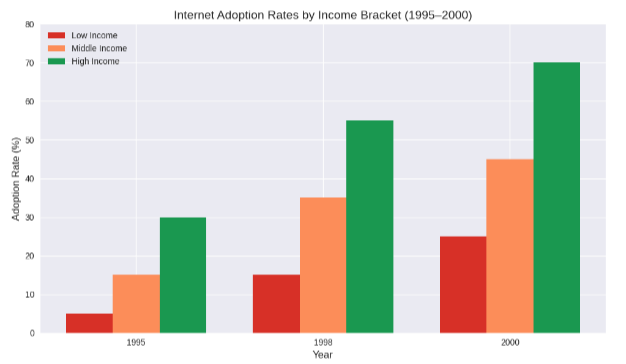

Class and income were among the strongest predictors of internet access in the 1990s, with NTIA’s Falling Through the Net reports consistently showing that wealthier households were far more likely to own computers and subscribe to internet services than low-income households. This divide reflected not only the cost of hardware and monthly service fees but also broader socioeconomic inequalities. For families struggling with basic needs, investing in a computer and dial-up subscription was often out of reach, while higher-income households could more easily adopt new technologies as they emerged.

Computer and internet adoption rates by income level during the early internet era.

The modern internet emerges as ARPANET transitions to the TCP/IP protocol, unifying previously separate networks.

Tim Berners-Lee’s World Wide Web launches publicly, opening the door for rapid growth in sites and online information.

Mosaic introduces a more user-friendly, graphical way to navigate the Web, making online access more appealing — for those who can get online.

A series of federal reports documents growing gaps in access by geography, race, and income, naming the problem as the “digital divide.”

President Clinton’s State of the Union calls for national action to close the digital divide, pushing the issue into mainstream policy debates.

The legacy of the 1990s digital divide continues to shape debates about equity and access today. In the decades since, the digital divide has evolved but not disappeared. Broadband replaced dial-up, mobile devices expanded connectivity, and adoption rates rose across all demographics. Yet NTIA’s later surveys and Pew Research Center studies show persistent gaps: rural households remain less likely to have high-speed broadband, low-income families struggle with affordability, and racial disparities in access and digital skills continue.

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored these divides, as students without reliable internet were left behind in remote learning, and workers without connectivity faced barriers to employment. The challenges identified in the 1990s remain relevant, although the technologies have changed.

Today, the digital divide is framed as a broadband equity issue, with policy efforts focused on universal access, affordability, and digital literacy. Federal programs such as the Affordable Connectivity Program and ongoing rural broadband expansion echo the goals of the 1990s but with updated tools. The legacy of the early divide reminds policymakers that access is not just about infrastructure — it is about ensuring that all communities, regardless of geography, race, or income, can fully participate in the digital economy.

The digital divide of the 1990s revealed how geography, race, and income shaped who could access the internet — and who was left behind. Despite investments in schools, libraries, and rural infrastructure, NTIA’s data made clear that barriers persisted, laying the foundation for today’s broadband equity debates. As we look back, the lessons of that decade remind us that technology alone cannot guarantee inclusion; only deliberate policies and sustained commitment can ensure that every community shares in the opportunities of the digital age.